Antoine Lavoisier was completely brilliant. He discovered water was composed of hydrogen and oxygen, and oxygen was involved in combustion. His pièce de résistance was proving the law of conservation of mass in chemistry. For this, he carefully measured the mass of reactants and products in many different chemical reactions within sealed jars. Et voilà! in every case, the total mass of the jar and its contents was the same after the reaction as it was before the reaction took place.

To fund his laboratory experiments, he became involved with the

hated Ferme Générale, a for-profit tax collection agency which reaped taxes for

the monarchy in return for the right to collect the taxes. On behalf of the Ferme

Générale, Lavoisier proposed a jar around Paris. He devised and commissioned

the building of a wall around Paris so that customs duties could be extracted from

those transporting goods into and out of the city at toll booth checkpoints.

Unfortunately, for Lavoisier he failed to predict the combustible situation the

jar would provoke. The people revolted, Bastille was stormed, and the bloodthirsty

mob hungry for revolution was set loose and came after him.

When he was sentenced to the guillotine in the French

Revolution for his role in tax collection efforts, Lavoisier decided his death

would be his last experiment. Lavoisier wondered how long a head could retain

consciousness after being severed from the body. He had heard of stories of

severed heads looking around, saying prayers, or expressing unequivocal

indignation when their faces were slapped etc…. He told his friend, “Watch my

eyes after the blade comes down. I will continue blinking as long as I retain

consciousness.” Lavoisier blinked for 15 seconds.

Claude Ledoux, the architect who designed the 55 toll

collection booths for the wall around Paris, met a fate slightly better than

Lavoisier’s. His head was spared, but his career was axed. With all his rich

clients exiled to other countries, imprisoned, or decapitated, Ledoux never got

the opportunity to build another building. Clientless and restless at the

height of his career, Ledoux shifted his focus to designing a utopian city with

futuristic visions of communal life and industrial urbanism.

Like Piranesi, Ledoux had started his professional life as

an engraver before entering architecture, so working on architectural

renderings was a return to his previous life before architecture. Two years

before his death in 1804, Ledoux published Architecture Considérée Sous le

Rapport de l’art, de Moeurs et de la Legislation which translates into the catchy

English title “Architecture Considered in Relation to Art, Customs and

Legislation”.

A more accurate title of the book should’ve been “The Ideal

City of Chaux: Where Fantasy Meets Reality.”

Fifteen years before the revolution, Ledoux had designed and built the

Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans near the forests of Chaux. The complex of Saltworks buildings would

become the starting point for the project of a Utopian city.

Before proceeding with insightful architectural analysis of

Ledoux’s Saltworks, for those readers unfamiliar with 18th century salt

production practices within the pre-revolutionary French political economy,

I’ll try to sum it up in a 4 short paragraphs.

To make salt, the French found and collected underground

saline water sources, cut down trees to make fires and boiled off the water in

boiling pans in 18 day shifts. It took teams of men to manage the boiling pans.

For 8-9 boiling pans, a brigade of 100 people was needed: shifts of 2 people to

skim the pot, 4 people to fire the stoves, 4 people to supply the wood, 4

workers to fire the stove. Over the course of an 18 day shift, the fire had to

be maintained at a continuous temperature, otherwise the quality of the salt

would be compromised. Barrel makers were

employed to create containers to store salt. Blacksmiths and carpenters were

constantly on call fixing and adjusting equipment. Salt making was a precise

work.

If the salt extraction process sounds tedious, consider all

the nauseating layers of control the French imposed on production: (1) tax

collecting agencies for salt commerce (2) controllers of the extraction process

(3) porters to register entry and exit and control the gates (4) controller of

salt stocks (5) receiver to distribute the salt from each factory (6) director

of salines (7) inspectors of wood (8) inspectors of work and maintenance (9)

architecture inspectors (10) inspector general of the water pumps and wells

(11) head of commerce of the Lorraine region and the (11) the King who used the

tax money to fund his lavish lifestyle.

It's not surprising the etymological origins of the words ‘bureaucracy’

and ‘revolution’ are both derived from French. Bureau means "desk with

drawers for papers, writing desk," in French and '-cracy' is the French form of

the Greek root word ‘-kratia’ which means "power, might; rule,

sway; power over; a power, authority. Revolution originally entered the French

vocabulary in the 13th century to describe the ‘rotation of celestial bodies

about the earth’ and was derived from the Latin word ‘ revolutio’ which

means "a turn around". By the 18th century ‘revolution’s meaning in

French evolved into ‘the fundamental and relatively sudden change in political

power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts

against the government, typically due to perceived oppression (political,

social, economic) or political incompetence.

That is, in 1700’s France, people got pissed off and ready

for revolution when they tried to make salt and had to endure 11 layers

of annoying governmental bureaucracy and various taxations to sprinkle

it on their food.

Now, back to the purpose of this blog, useless guillotine

trivia architectural scholarship… in 1771, Ledoux was appointed inspector

of Saltworks at the Arc de Senans in eastern France. Up to that point, the town’s

salt factory was in the mountains near the source of underground saline water. When

wood used to fuel the saline water burning pans became scarce, Ledoux started working

on a Utopian vision with no particular site in mind.

Untethered to reality, he proposed constructing a 20 km canal

of wooden pipes from the saline source to the edge of a nearby forest where

wood was abundant. He reasoned it would be easier to bring the salt water to

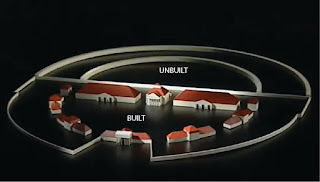

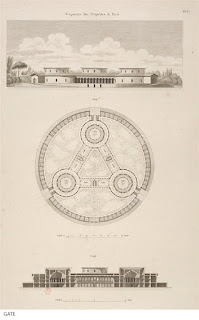

the boiling pan rather than wood to the fire. Semicircular in plan, and crystalline in

geometry, the Saltworks “as pure as that described by the sun along its transit”

would be planted like a seed next to the forest. The industrial production and

hierarchical organization of the Saltworks would then sprout and sponsor the

growth of an Ideal City.

Ledoux presented his Saltworks visions to King Louis XV in

1773. The King personally approved Ledoux’s plan and the Saltworks became built

reality in 1779. Within 10 years, however, the Saltworks was abandoned after

the French Revolution erupted in 1789. Unfortunately, since the complex was

funded by the monarchy, Ledoux’s work was perceived as a symbol of the “Ancien

Régime” and the Ideal City he envisioned was never built. Over the centuries, the

Saltworks were used as a military barracks, camp for Spanish refugees and as a Nazi

concentration camp for gypsies.

Today, one can visit the site and experience how distinctive

Ledoux’s vision was. The central entry to the walled site is a Doric column

portico. Compared to the typical ornate baroque bullshit architecture of

his time, this was quite unusual and sober in the 1790s. Doric is archaic and

rough. Ledoux then transitions the Doric columns into an artificial primordial stone

grotto cave opening that funnels visitors through a neo-classical guardhouse opening

onto a semicircular lawn on axis with the director’s pavilion which has bizarre

columns composed of alternating round and square stones... Upon this entry sequence

into the Saltworks, Ledoux has transported you into some sort of alternate

reality.

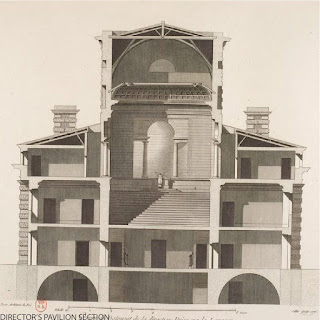

The round window in the pediment of the looming director’s pavilion

looks like a giant eye - nothing within this Saltworks compound escapes

surveyance. “Don’t even think of pilfering salt from the premises.” Along the

arc, communal housing is arranged for the salt worker brigades. Flanking the director’s

pavilion symmetrically are workshop factories and pavilions for tax clerks. Ascend

the monumental stairs within the director’s pavilion and you find yourself at

the foot of a priest in a chapel bathed in mysterious light who recites a prayer

in a creepy French accent. “Je crois en Sel, le Pere tout-puissant, créateur du

ciel et de la terre. Amen.”

The 1800s didn’t understand or appreciate Ledoux’s Classicism

nor his modernity but 20th century architects rediscovered Ledoux and

recognized his clairvoyance. 140 years before 1920’s Bauhaus buildings and

Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse, Ledoux was designing for industrialization in the new

age of mass production. Whereas a traditional Baroque solution to the Saltworks

would have been one large ornate complex housing all the activities of

production (i.e., Versailles), in the Saltworks, functions were zoned separated

into 11 discrete buildings: 4 communal housing, 1 gate, 1 director, 1 stable, 2

tax clerks, and 2 workshops.

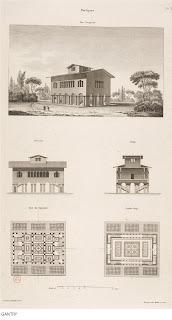

Look beyond the surface of classical porticos and stone

material, and you’ll notice each of Ledoux’s buildings are treated in quite a modern

fashion in that they are specialized, articulated, and differentiated in terms

of their height, floor to floor clearances, façade treatments, roof, fenestration.

The housing featured shared double height centralized communal dining and

kitchen spaces to economize on wood for the hearths and foster social interaction.

Behind the housing, gardens were allocated to the residents for private use. Connections

between buildings were minimized to minimize the risks to fire, and to break

the scale of buildings down within the campus.

The salt workshop facilities had vents disguised as dormer

windows. Landscaped area behind workshops were dedicated to storing wood for fuel.

Large long span timber roof construction housed the boiling pan assemblies

below. Internal layouts were repeated, to optimize salt production and processing.

To reinforce efficient administration, the director’s building was centrally

positioned to oversee all workers on site. Circulation routes cut through all administration

buildings to ensure direct flows of salt.

To create a cohesive plan, Ledoux recognized the importance of

tying all Saltworks buildings together with ornamentation, recognizable building

typologies, and strong geometries. Stone ornamentation on buildings depict salt

flowing from urns, thereby indicating the principal function of the buildings within.

Entries to facades along the semicircular central court area are rusticated and

emphasized to mark their significance. The simple geometries of the landscape

and buildings are in harmony. Ledoux’s goal was to use architecture to shape a

society and create a collective spirit, while emphasizing work as the ultimate

value at the center of human activity.

At the back of the director’s pavilion, the stables open onto a small back gate. It was through this passage that Ledoux imagined the connection to the rest of his Ideal City of Chaux which would’ve mirrored the semicircular Saltworks in plan to form a complete circle. In the barren field, one can contemplate the complete world of what could have been, replete with all the unbuilt designs for a bridge, market place, graveyard, artillery building, school building, and housing types for coopers, blacksmiths, and lumberjacks, Temple of Memory, and even a brothel that Ledoux was allowed to dream in the last years of his life but not build.

Awesome Detailed Blog

ReplyDeleteTry Reaching Out To Us

contemporary aluminum railings

it is a good article post. thanks for shareing.

ReplyDeleteKitchen Remodeler In San Jose

kitchene remodeling bay area

kitchen remodeling san jose california

general contractor in san jose ca

home remodel san jose

san jose home remodel

home builders in the bay area

general constractors san jose california

general contractors in the bay area

construction companies in the bay area

bay area contractors

construction companies in San Jose

bathroom remodel San Jose

general contractor San Jose

Waterproofing chemical keeps an object or structure safe from water damage and moisture. Keep your surface save from water damage, you can take waterproofing service from us.

ReplyDelete