Yoko recounted a story of lennon making tea in the New York Times 10 years ago:

“John and I are in our Dakota kitchen in the middle of the night. Three cats Sasha, Micha and Charo are looking up at John, who is making tea for us two.

Sasha is all white, Micha is all black. They are both gorgeous, classy Persian cats. Charo, on the other hand, is a mutt. John used to have a special love for Charo. “You’ve got a funny face, Charo!” he would say, and pat her.

“Yoko, Yoko, you’re supposed to first put the tea bags in, and then the hot water.” John took the role of the tea maker, for being English. So I gave up doing it.

It was nice to be up in the middle of the night, when there was no sound in the house, and sip the tea John would make. That night, however, John said: “I was talking to Aunt Mimi this afternoon and she says you are supposed to put the hot water in first. Then the tea bag. I could swear she taught me to put the tea bag in first, but ...”

“So all this time, we were doing it wrong?”

“Yeah ...”

We both cracked up. That was in 1980. Neither of us knew that it was to be the last night of our life together.

On this day, 30 years ago the day he was assassinated, what I remember is the night we both cracked up drinking tea.

They say teenagers laugh at the drop of a hat. Nowadays I see many teenagers sad and angry with each other. John and I were hardly teenagers. But my memory of us is that we were a couple who laughed.

Kakuzo published his Book of Tea in 1906, 2 years before the advent of the tea bag and 74 years before lennon’s death, so he wasn’t able to document the modern evolution of tea. In 1908, Thomas Sullivan, a New York tea merchant, started to send samples of tea to his customers in small silk bags. Some customers assumed that these were supposed to be used in the same way as the metal infusers, by putting the entire bag into the pot, rather than emptying out pouch’s contents into the water. It was thus by accident that the tea bag was born. Responding to the comments from his customers that the mesh on the silk was too fine, Sullivan developed tea bags made of gauze with a string with a decorated tag to facilitate removal. During the 1920s these were developed for commercial production, and the bags grew in popularity in the USA. During the 1950s in the UK tea bags gained popularity on the grounds that they removed the need to empty out the used tea leaves from the tea pot. it was during this era that lennon learned how to make tea from his aunt mimi. Now 96% of the tea made in Britain is via teabag.

Leave it to the labor saving Americans to develop tea bags. No kneeling on a tatami mat, whisking powdered tea, or contemplation of life needed. just dunk a tea bag in some luke warm water and voila! Leave it to the pedantic british to ponder the correct sequence of actions of making tea with tea bags. Kakuzo probably would’ve been horrified by Sullivan’s thoughtless automation and mass production of the tea making process and found lennon’s ‘insert tea bag after water is poured’ epiphany imbecilic. Or perhaps, like a true teaist, Kakuzo would laugh. “The ancient sages never put their teachings in systematic form. They spoke in paradoxes, for they were afraid of uttering half-truths. They began by talking like fools and ended by making their hearers wise. Laotse himself, with his quaint humour, says, "If people of inferior intelligence hear of the Tao, they laugh immensely. It would not be the Tao unless they laughed at it." After all, kakuzo proposed, “Teaism was Taoism in disguise.”

As an aetheist I have trouble keeping track of religions. Some believe in days of atonement, others fast for a month, some set up a pine tree and put gifts underneath it purportedly delivered from a fat bearded white guy in a red clothing sliding down a chimney, some fast for a week and eat unleavened crackers, some sanction the consumption of pork, some ban the eating of a chicken and egg together, some require getting piss drunk and yelling “yankees suck, redsox rule”… it’s all very confusing to an aetheist. Rather than define Taoism first and then proceed to academically show how perriand was Taoist in design philosophy, I find it easier to learn about Taoism anecdotally through her design process.

“Yoko, Yoko, you’re supposed to first put the tea bags in, and then the hot water.” John took the role of the tea maker, for being English. So I gave up doing it.

It was nice to be up in the middle of the night, when there was no sound in the house, and sip the tea John would make. That night, however, John said: “I was talking to Aunt Mimi this afternoon and she says you are supposed to put the hot water in first. Then the tea bag. I could swear she taught me to put the tea bag in first, but ...”

“So all this time, we were doing it wrong?”

“Yeah ...”

We both cracked up. That was in 1980. Neither of us knew that it was to be the last night of our life together.

On this day, 30 years ago the day he was assassinated, what I remember is the night we both cracked up drinking tea.

They say teenagers laugh at the drop of a hat. Nowadays I see many teenagers sad and angry with each other. John and I were hardly teenagers. But my memory of us is that we were a couple who laughed.

Kakuzo published his Book of Tea in 1906, 2 years before the advent of the tea bag and 74 years before lennon’s death, so he wasn’t able to document the modern evolution of tea. In 1908, Thomas Sullivan, a New York tea merchant, started to send samples of tea to his customers in small silk bags. Some customers assumed that these were supposed to be used in the same way as the metal infusers, by putting the entire bag into the pot, rather than emptying out pouch’s contents into the water. It was thus by accident that the tea bag was born. Responding to the comments from his customers that the mesh on the silk was too fine, Sullivan developed tea bags made of gauze with a string with a decorated tag to facilitate removal. During the 1920s these were developed for commercial production, and the bags grew in popularity in the USA. During the 1950s in the UK tea bags gained popularity on the grounds that they removed the need to empty out the used tea leaves from the tea pot. it was during this era that lennon learned how to make tea from his aunt mimi. Now 96% of the tea made in Britain is via teabag.

Leave it to the labor saving Americans to develop tea bags. No kneeling on a tatami mat, whisking powdered tea, or contemplation of life needed. just dunk a tea bag in some luke warm water and voila! Leave it to the pedantic british to ponder the correct sequence of actions of making tea with tea bags. Kakuzo probably would’ve been horrified by Sullivan’s thoughtless automation and mass production of the tea making process and found lennon’s ‘insert tea bag after water is poured’ epiphany imbecilic. Or perhaps, like a true teaist, Kakuzo would laugh. “The ancient sages never put their teachings in systematic form. They spoke in paradoxes, for they were afraid of uttering half-truths. They began by talking like fools and ended by making their hearers wise. Laotse himself, with his quaint humour, says, "If people of inferior intelligence hear of the Tao, they laugh immensely. It would not be the Tao unless they laughed at it." After all, kakuzo proposed, “Teaism was Taoism in disguise.”

As an aetheist I have trouble keeping track of religions. Some believe in days of atonement, others fast for a month, some set up a pine tree and put gifts underneath it purportedly delivered from a fat bearded white guy in a red clothing sliding down a chimney, some fast for a week and eat unleavened crackers, some sanction the consumption of pork, some ban the eating of a chicken and egg together, some require getting piss drunk and yelling “yankees suck, redsox rule”… it’s all very confusing to an aetheist. Rather than define Taoism first and then proceed to academically show how perriand was Taoist in design philosophy, I find it easier to learn about Taoism anecdotally through her design process.

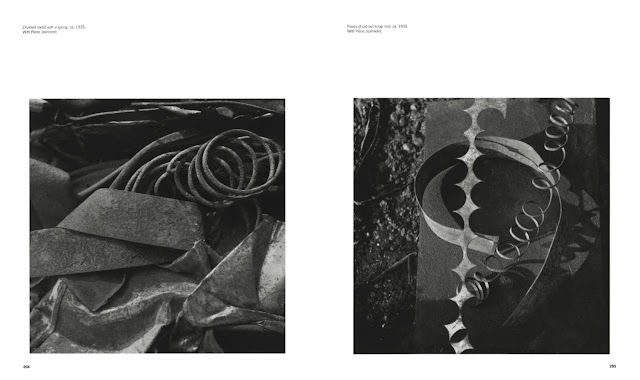

Perriand used the whimsical expression ‘l’oeil en eventail’ (a wide-angle eye) to refer to an important aspect of her creative process. She payed attention to every object, humble or striking, large or small, man-made or natural, and learning the lesson it had to teach. Perriand would take photos (ie., double wood trunk rings) and have them inspire forms (i.e., stove in refuge tonneau).

In the 1930s, Perriand, artist Fernand Léger, and Pierre Jeanneret enjoyed weekend expeditions to the Normandy beaches. “We would fill our backpacks with treasures: pebbles, bits of shoes, lumps of wood riddled with holes, horsehair brushes—all smoothed and ennobled by the sea,” she recalled in her 1998 autobiography. “We sorted them, admiring them, soaking them in water to give them more of a shine, and taking photographs. We called it our art brut.”

|

| Dubuffet's art brut |

To perriand, “Architecture is an ebb and flow between interior and exterior—a round-trip”… life like architecture, is a journey – they are inseparable. ''in every important decision there is one option that represents life, and that is what you must choose.''

Perriand's outlook on life is aligned with how Kakuzo presents Tao. "Tao is the Passage rather than the Path. It is the spirit of Cosmic Change,—the eternal growth which returns upon itself to produce new forms. It recoils upon itself like the dragon, the beloved symbol of the Taoists. Taoist Absolute was the Relative. In ethics the Taoist railed at the laws and the moral codes of society, for to them right and wrong were but relative terms. "art of being in the world… Relativity seeks Adjustment; Adjustment is Art. The art of life lies in a constant readjustment to our surroundings. Taoism accepts the mundane (i.e., graffiti and flotsam perriand photographed) as it is and, unlike the Confucians or the Buddhists, tries to find beauty in our world of woe and worry. The Sung allegory of the Three Vinegar Tasters explains admirably the trend of the three doctrines. Sakyamuni, Confucius, and Laotse once stood before a jar of vinegar—the emblem of life—and each dipped in his finger to taste the brew. The matter-of-fact Confucius found it sour, the Buddha called it bitter, and Laotse pronounced it sweet.”

Perriand’s mind was flexible. Unable to return to France during the war, she entertained ways to re-consider materials from Kakuzo's prodding "To European architects brought up on the traditions of stone and brick construction, our Japanese method of building with wood and bamboo seems scarcely worthy to be ranked as architecture." Perriand would later remark, “I saw some sugar tongs made from bamboo, created by the Institute of Tokyo, and it gave me the idea to transpose the stainless steel chaise longue from 1928, using the flexibility of machined bamboo instead of steel”, she writes in A Life of Creation. While wandering through cities like Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka and exploring the Japanese countryside in order to select “objects worthy of being exported, Perriand discovered not only the art of living in Japan, but also the art of inhabiting. “In Japan, which was 100% traditional at the time, I discovered emptiness, the power of emptiness, the religion of emptiness, fundamentally, which is not nothingness. For them, it represents the possibility of moving. Emptiness contains everything”, she explained to France Culture on Mémoires du siècle in 1997.

Having never been to Japan myself, I don’t perfectly understand perriand’s fixation on emptiness. given america’s out of control covid situation, I predict I’ll be banned from Japan for the next several years, so i'll have to rely on Kakuzo’s insight on emptiness for now.

“Laotse illustrates emptiness by his favourite metaphor of the Vacuum. He claimed that only in vacuum lay the truly essential. The reality of a room, for instance, was to be found in the vacant space enclosed by the roof and the walls, not in the roof and walls themselves. The usefulness of a water pitcher dwelt in the emptiness where water might be put, not in the form of the pitcher or the material of which it was made. Vacuum is all potent because all containing. In vacuum alone motion becomes possible. One who could make of himself a vacuum into which others might freely enter would become master of all situations. The whole can always dominate the part. These Taoists' ideas have greatly influenced all our theories of action, even to those of fencing and wrestling. Jiu-jitsu, the Japanese art of self-defence, owes its name to a passage in the Tao-teking. In jiu-jitsu one seeks to draw out and exhaust the enemy's strength by non-resistance, vacuum, while conserving one's own strength for victory in the final struggle. In art the importance of the same principle is illustrated by the value of suggestion. In leaving something unsaid the beholder is given a chance to complete the idea and thus a great masterpiece irresistibly rivets your attention until you seem to become actually a part of it. A vacuum is there for you to enter and fill up the full measure of your aesthetic emotion. He who had made himself master of the art of living was the Real man of the Taoist. At birth he enters the realm of dreams only to awaken to reality at death. He tempers his own brightness in order to merge himself into the obscurity of others. He is "reluctant, as one who crosses a stream in winter; hesitating as one who fears the neighbourhood; respectful, like a guest; trembling, like ice that is about to melt; unassuming, like a piece of wood not yet carved; vacant, like a valley; formless, like troubled waters." To him the three jewels of life were Pity, Economy, and Modesty.”

No comments:

Post a Comment