Small contractors worked with a limited amount of capital and couldn’t take advantage of large- scale production that the CHC utilized. The revolving capital fund that the CHC set up provided a firm financial foundation for the construction of a network of garden cities. The bulk of profits from house sales were poured back to the community. To keep carrying costs to a minimum, CHC exercised rapid construction. The CHC would commence construction soon after land was purchased and built throughout the year.

RPA’s affiliation with the CHC enabled the realization of urban projects. While the Garden Cities Association in England, was primarily concerned with the regional development around a metropolitan area (London), the RPA was engaged in plans for the development of the region around New York City. The CHC was the vehicle that the RPA used to promote housing reform. Bing hoped that as the CHC grew, the financial reserves could be built up and further experiments and research in town planning could be undertaken. Sunnyside and Radburn were not goals, they were part of a larger regional plan. In Lewis Mumford’s words, the “Radburn idea was a finger exercise preparing for the symphonies that are yet to come” [9]

Sunnyside

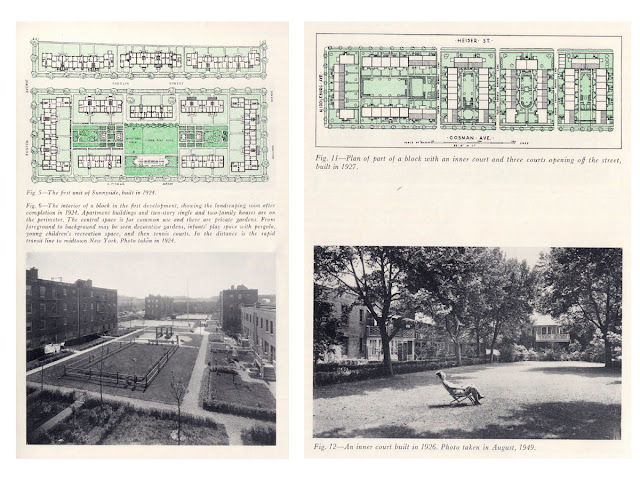

In February 1928, the City Housing Corporation purchased 77 acres of undeveloped land in Queens which had been held by the Long Island Railroad. Between 1924-1928, 1202 family units were constructed. The land at Sunnyside was cheap at 50 cents per square foot. The commute from Sunnyside to Manhattan took only 15 minutes. Since Sunnyside was built in an industrial area, with no existing residential zoning, the planners had more freedom to find an alternative to the grid iron city where 25 by 100 foot lots were the norm. Sunnyside’s planners tried to develop within the rigid framework of New York City’s gridiron street layout of 200 by 600 to900 foot blocks. In 1923, studies of gridiron cities done by the members of the RPA, showed the costliness of gridiron layout. Stein commented that at Sunnyside, the planners were “Forced to fit the building to the blocks rather than the living conditions to the blocks.” [10]

The Sunnyside superblock can be characterized typologically by its amenity core and service routes. The amenity core is surrounded with a perimeter of narrow residences. The amenity core, which is 120 feet wide, contains a common garden space and private gardens for use by residents. Each house has a private garden 30 feet deep. Livingrooms and bedrooms face the gardens instead of the streets.

Between the 3 family buildings, service pathways cross from street to street and give access to the center of blocks. These alleyways were designed for delivery of coal, ice and food to the rear of the houses. Services enter directly to kitchen cellar entrance by private paved service lanes.

Lewis Mumford who lived in Sunnyside for 11 years wrote, “it has been framed to the human scale and its gardens and courts kept that friendly air as year by year, the newcomers in the art of gardening and the plane trees and poplars continues to grow. So though our means were modest, we continued to live in an environment where space, sunlight, order, color, these essential ingredients for either life or art were constantly present, silently molding all of us.” [11]

A 1928 census of houseowners at Sunnyside indicated that a diversity of residents inhabited Sunnyside. There were 116 mechanics, 79 office workers, 55 small tradesmen, 5 chauffeurs, 49 salesmen, and numerous actors, artists, musicians, teachers, engineers, doctors and other professionals. The residents were of moderate means. The people of Sunnyside were accustomed to meeting and doing things together.

The construction operations at Sunnyside were well managed. Each unit of building was completed without leaving vacant lots, and utilities were installed as needed. Homes were sold and rented as soon as they were completed. At Sunnyside, the CHC was able to accrue enough profit to establish a revolving capital pool. By 1928, 1202 units were sold at Sunnyside at $300,000 profit. Only 55 of the 77 acres used were built. The extra 22 acres were sold for an additional $646,786 profit on undeveloped ‘ripened’ land. The CHC was the beneficiary of the speculative market. The CHC used the surplus revenues to initiate the Radburn project.

The ideas of open space and service routes at Sunnyside were further developed at Radburn. At Sunnyside, the planners proved large open spaces could be preserved in block centers with reduced capital investment if planned properly. The planners went on to create even larger open space cores in the Radburn plan. Additionally, service alleys, which opened off the streets of Sunnyside, suggested methods of introducing cul-de-sacs to the superblock at Radburn.

Radburn in England

Although Radburn didn’t have much influence on American town planning, it did significantly impact English planning in the 1950’s. “The Town Development of the Greater London Council has produced internal memoranda upon which the housing area planners could base their development concepts; some of these have incorporated, as a criterion for the pattern of housing areas, pedestrian-vehicle separation.” [12] Twenty-eight new towns (including Stevenage, Bracknell, Cumbernauld Basildon, Harlow, Peterlee, Beeston, and Nottingham) adhering to Radburn principles were built in England since 1946 when they adopted a new towns policy.

These new towns differ from Radburn in many regards. The new towns in England had much higher populations (100 to 250,000 residents). The efforts of the new towns were concentrated on accodomating metropolitan growth and meeting housing needs rather than the creation of a network of self-sufficient towns. Unlike Radburn, land in the new towns in England was not privately owned. The New Towns Act of 1946 passed by Parliament expanded the government’s role in town planning. Under the New Towns Act, the development corporations borrowed money from central government with all profits returned to central government. The central government was the landlord. Additionally, through the Industrial Selection Scheme, job applicants were matched with jobs in new towns; housing was made available to those that worked in the town. Under Thatcher, however, the socialist aspect of new towns was discontinued. Publicly held assets of new towns were sold to private interests. Furthermore, after 1970, no new towns were designated.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, Radburn shows us the potential in challenging the basic notions of housing development. Planners can challenge the existing division of land lots and grid-iron street patterns to achieve housing clustered at higher density with different social configurations. If planners are able to plan the street systems wisely, enough money can be saved on infrastructure to fund the open space. At Radburn, public open space necessitates community organizations to govern the open space. This shows the potential for a physical plan to generate community involvement. This integrated approach to planning (which can be seen in the work of contemporary planners such as Field Operations) deserves further study.

In studying Radburn it is valuable to not only look at the physical manifestation of the plan, but at the intentions and regional planning motivations involved in its conception. Many of the problems, such as unchecked suburban sprawl, faced by Radburn’s planners, are contemporary planning issues. Radburn offers planners today examples of approaches, alternatives, and solutions to speculative housing development (i.e., limited dividend corporation development). There are many lessons to be learned through the successes and failures of Radburn. For example, the experience at Radburn shows the necessity of strong finances in order to execute a plan and its social intentions. Affordable housing needs limited dividend non-profit organization or public subsidy. As shown in England, government policies have a great influence in the realization of town planning.

Bibliography

10. “A New Lease on Living”. City Housing Corporation. N.Y., The Corporation. 1928

11. “Radburn Garden Homes / City Housing Corporation”. New York : City Housing Corporation, [1930 printing]

12. “Regarding Radburn. [Press notices.]” City Housing Corporation. N.Y., The Corporation. 1928

13. “Radburn A town planned for Safety” American Architect 1930 Jan. v. 137 p 42-45

14. Schaffer, Daniel. Garden Cities for America: The Radburn Experience Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982

15. Stein, Clarence. “Housing and the Depression”. The Octagon June 1933.; p. 3-7.

16. Stein, Clarence. “A New Venture in Housing.” The American City Magazine, March 1925;p.277-281.

17. Stein, Clarence and Bauer, Catherine. “Store Building and Neighborhood Shopping Centers” Architectural record, Feb. 1934; vol. 75, no. 2, p. 175-187; with photos, diagrs., tables.18. Stein, Clarence Toward New Towns for America. University Press of Liverpool; agents for the Western Hemisphere: Public Administration Service, Chicago, 1951.

19. United States Shipping Board. Emergency Fleet Corporation Housing the shipbuilders. Construction during the war, under the direction of United States Shipping Board, Emergency Fleet Corporation, Philadelphia, PA: Passenger Transportation and Housing Division, 1920

20. Unwin, Raymond. “Nothing Gained by Overcrowding”. Garden Cities and Town Planning Association. Leaflets, [Nov. 1932], 4 p.; with photos., diagrs.

21. Wright, Frank Lloyd, “Broadacre City: a new community plan”. Architectural record, Apr. 1935; vol. 77, p. 243-252; with photos., photos. of models, plan.

22. Wright, Henry N. “The Architect and Small House Costs.” Architectural record, Dec. 1932; p. 389-395.

23. Wright, Henry N. “Radburn Revisited” Ekistics, March 1972, vol. 33:196, pp. 196-201; with illus

24. Wright, Henry. “The Autobiography of Another Idea” Western Architect September 1930 vol. 30, p137-141, 153. by the RPA. NYC

No comments:

Post a Comment