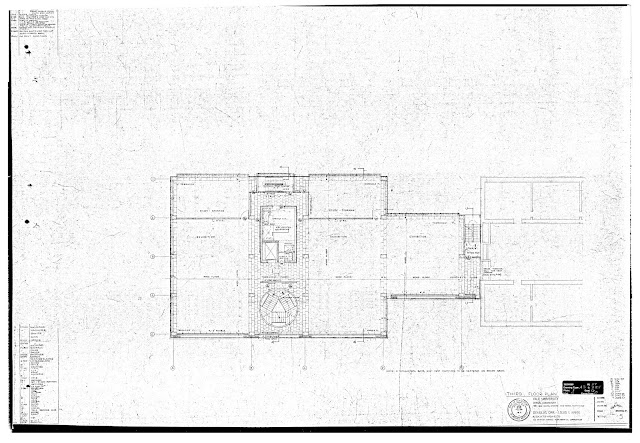

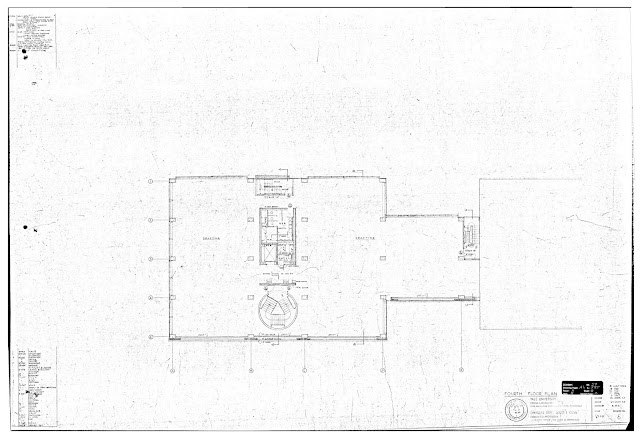

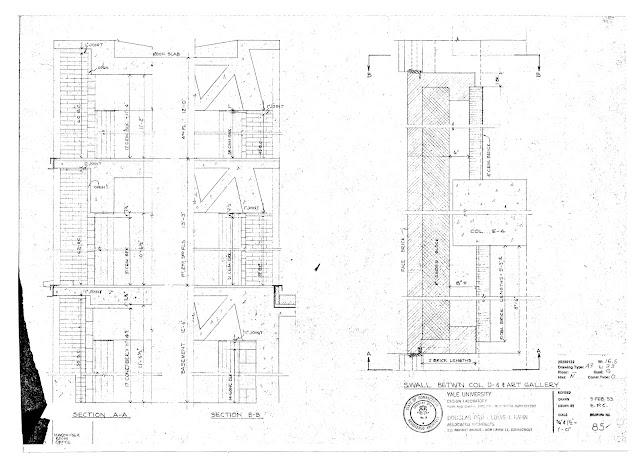

In plan, the Yale Art Gallery has a central core that is flanked by 2 open spaces, each 40'x80' long. Within the central core, the fire stairs, elevators, mechanical shafts, and toilets are gathered in a central zone away from the perimeter. The diagrammatic clarity of the plan is reinforced spatially by the building structure. The core acts like a trunk of a tree carrying services vertically. The ducts and electrical raceways are threaded through the distinctive concrete tetrahedral ceiling that branch east and west. There is a distinction between the 'servant' and 'served' spaces - a spatial hierarchy. The narrower towards the eastern portion of the building is the link between the old academic buildings and the new building.

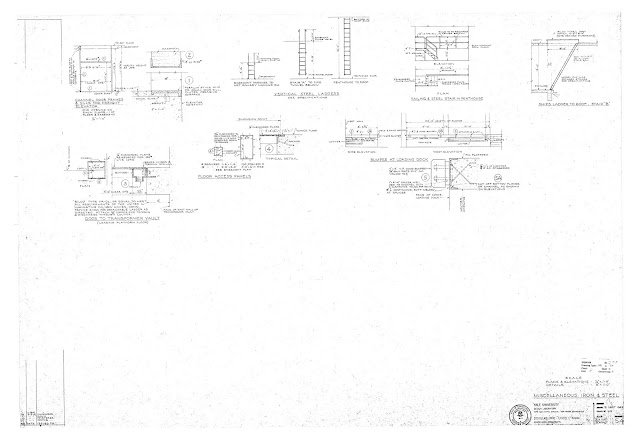

Each material in the building serves a role. Reinforced concrete forms the structural frame, columns, girders, structural slab, and the hollow cylindrical column of the main stair. It is the least refined. today, you can see the narrow boards of the wood formwork which are visible on the surface of the concrete.

Steel and glass curtain wall clads the north side of the building. Face brick on the east is mounted to 4"x6" concrete block which is exposed on the interior. Within the central core, a cylindrical concrete stair announces its importance since its geometry contrasts with the rectangular and triangular forms of the building. terrazzo is used a a floor finish at the entrance and in the core. Each material decision in the Art Gallery follows a systematic way of thinking. there is a logic behind each decision.

Steel and glass curtain wall clads the north side of the building. Face brick on the east is mounted to 4"x6" concrete block which is exposed on the interior. Within the central core, a cylindrical concrete stair announces its importance since its geometry contrasts with the rectangular and triangular forms of the building. terrazzo is used a a floor finish at the entrance and in the core. Each material decision in the Art Gallery follows a systematic way of thinking. there is a logic behind each decision.

Despite the clarity in thought, i would later learn the building and architect were far from perfect. when i was at polshek, i worked with a couple architects in charge of the renovation of the Yale Art Gallery. The glass curtain wall was mounted between the concrete floor slabs without consideration of steel mullion thermal expansion movement. Over time, the material expansion put pressure on glass cracking the insulative seals thereby allowing condensation to build up over time. Polshek replaced the steel frame of the window wall with an aluminum one that is thermally broken by a synthetic material, so that the fluctuations in external temperature that previously resulted in condensation and corrosion have been minimized. New expansion joints installed throughout the building relieve the pressure that previously caused floor slabs to crack and glazing seals to fail.

In my last year, i saw a screening of a movie by Kahn's son, Nathaniel called My Architect at the British Arts Center. In the movie, Nathaniel, showed how unstable, secretive, chaotic, Kahn's personal life was. Kahn led a nomadic existence, always traveling in search of the next commission or to oversee work on far-off projects. To the outside world, he was happily married to Esther Israeli and raising a daughter, Sue Ann. When the architect died in 1974 of a heart attack, alone and destitute in the men's room at New York's Pennsylvania Station, he left behind three separate families who lived within miles of each other but never crossed paths until his funeral. Kahn hardly seemed the womanizing sort, but outside his marriage, he had long-term relationships with two other women who bore children by him. One was Anne Tyng, a talented architect who worked in Kahn's office for 10 years, on projects such as the Salk Institute. She had his daughter Alexandra. The other was Nathaniel's mother, who worked in Kahn's office on the Kimbell Art Museum, among other projects.

Tyng graduated from Radcliffe College in 1942, and was among the first women admitted to the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she studied architecture under Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Her classmates included Lawrence Halprin, Philip Johnson, Eileen Pei, I.M. Pei, and William Wurster. When 25-year-old Anne Tyng went to work for Philadelphia architect Louis I. Kahn in 1945, Kahn was a married man 19 years her senior. In 1954, Tyng gave birth to Alexandra Tyng, Kahn's daughter.

In his midlife tour to Europe for the Rome Prize residency, Kahn corresponded with Tyng about the epiphanies he saw in the ancient ruins of Greece, Rome and the Pyramids -- that the best buildings are those that combined bold geometries with the monumentality and mystery of ancient ruins with the expressive use of materials and natural light. Tyng was instrumental in helping Kahn refine the geometry of his projects. At the Yale Art Gallery, she is credited with the geometric order of tetrahedral ceiling. Of their relationship, Tyng said, "I believe our creative work together deepened our relationship and the relationship enlarged our creativity. In our years of working together toward a goal outside ourselves, believing profoundly in each other‘s abilities helped us to believe in ourselves."

Like the British Arts Center blog entry, all of Kahn's Yale Art Gallery building drawings are provided later in this post.

No comments:

Post a Comment